Maltese Folk Music: A Love Song To Malta's Living Musical Heritage

by Chiara Micallef

Slow, rhythmic and quasi-hypnotic, għana is traditional Maltese folk music made up of poetic verses and rhythmic guitar strums.

Some stipulate that għana is a descendant of Spanish and Sicilian singing, while others attribute its origin to the Arab rule in Malta. However, local historian Godfrey Wettinger, known for discovering the Kantilena, found that għana was first documented in the fifteenth century, attributing its birth to right around that time. Wettinger stated that għannejja regularly performed at noble weddings alongside musicians – debunking the Arab, Spanish and Sicilian influence theories.

Għana was looked at as a lower-class pastime belonging to farmers, fishermen, villagers and housewives – it portrayed a simpler life, as opposed to the Italian operas which dominated the musical scene for the upper circles of society and city-dwellers.

Għana In Literature

Francois-Emmanuel de Saint-Priest published a manuscript in 1791 titled Malte par un Voyageur François, in which he included three għana pieces – It-Tliet Għanjiet bil-Malti – as told to him by local librarian, priest and poet Gioacchino Navarro. These are the first ever printed poems in Maltese – not to be confused with Il-Kantilena, the oldest known literary text in the Maltese language.

The Maltese language has archaic origins, and over the years it forged a decadent library of proverbs to act as descriptors rather than adjectives and adverbs like the English language. Għana was the song of the illiterates – untrained musicians, singers and composers learned their craft by ear and used the song to show off their knowledge of the Maltese language.

Dun Karm Psaila drew a link between għana and Maltese poetry in his 1952 publication Antoloġija mit-Tliet Kotba tal-Għana, while Sant Cassia notes in his 1989 research titled L-Għana: Bejn il-Folklor u I-Ħabi, that għana always held an invulnerable role in regional customs and culture – almost a form of protest against the islands' many foreign rulers.

Musical Instruments

Għannejja were traditionally accompanied by multiple musicians who played the rabbaba (friction drum), iż-żaqq (bagpipe), it-tanbur (frame drum) and il-betbut (reed pipe) among others.

Għannejja nowadays are escorted by anywhere between one to three guitars modelled after the Spanish guitar, but smaller and with metal frets, turning keys and strings, decorated with ornamental motifs at the front.

The guitar players strum along with a dominant chordal progression, giving the song a sound neither Eastern nor Western, but something hovering in between – just like Maltese culture.

Types of Għana

Għana fil-Għoli

Also known as la Bormliża, this is the oldest musical form known in Malta. Local scholars and researchers promote evidence that għana fil-għoli is of indigenous origin and makes use of a particular local vocal dialect existing only in Malta.

La Bormliża was first developed to simulate early forms of għana exclusively sung by women, thus the male għannejja who partook in this singing style were required to reach remarkable levels of high soprano ranges without breaking into a falsetto. Due to its extreme and laborious demands, this style is very rarely practised nowadays.

American ethnomusicologist Marcia Herndon contended that one of the contributing factors for this style of għana's decline was the dominance of għannejja spirtu pront taking over the discourse with contemporary subjects which related more to the local audience.

Għana tal-Fatt

Unvarnished, at times melancholic and ballad-like, għana tal-fatt always recounts a story. Whether it is factual events, folktales or humorous incidents, this style is known to keep oral tradition alive, as it passes on anecdotes and chronicles from one generation to the next. This genre sensationally recounts historical events and aims to evoke feelings in the audience.

Għana Spirtu Pront

This is the most widespread style nowadays, with spirtu pront sessions being performed at local village feasts, każini, bars and popular folk events such as l-Imnarja regularly. These informal song duels are carried out by two or more għannejja who improvise their għana to demonstrate their knowledge and command of the Maltese language through elaborate use of wit, double entendre, rhyme, idioms and proverbs. At times they recount a story, while at other times they take friendly jabs at each other.

The Unconventional Għannejja

Women sang għana recreationally to while away the time as they completed household chores. These impromptu għana sessions began within the home, moved to the għajn tal-ħasselin where clothes were washed, and then progressed to household roofs, where the clothes were later hung out to dry.

Women were regularly heard conversing among themselves through għana – gossiping, circulating important news and sometimes even bickering – across the waist-high railings separating one home's roof from another. These women created an undivided community which communicated across the Maltese skyline, springs and their walled confines using għana.

Being resourceful as ever, the Maltese quickly turned għana from a pastime to a marketing tool, as hawkers used it to peddle their produce at local markets. Their inventive verses enticed customers, and while there is no evidence that it aided them in selling more of their produce, it surely made the tapestry of peasant life colourful.

Recorded Oral History

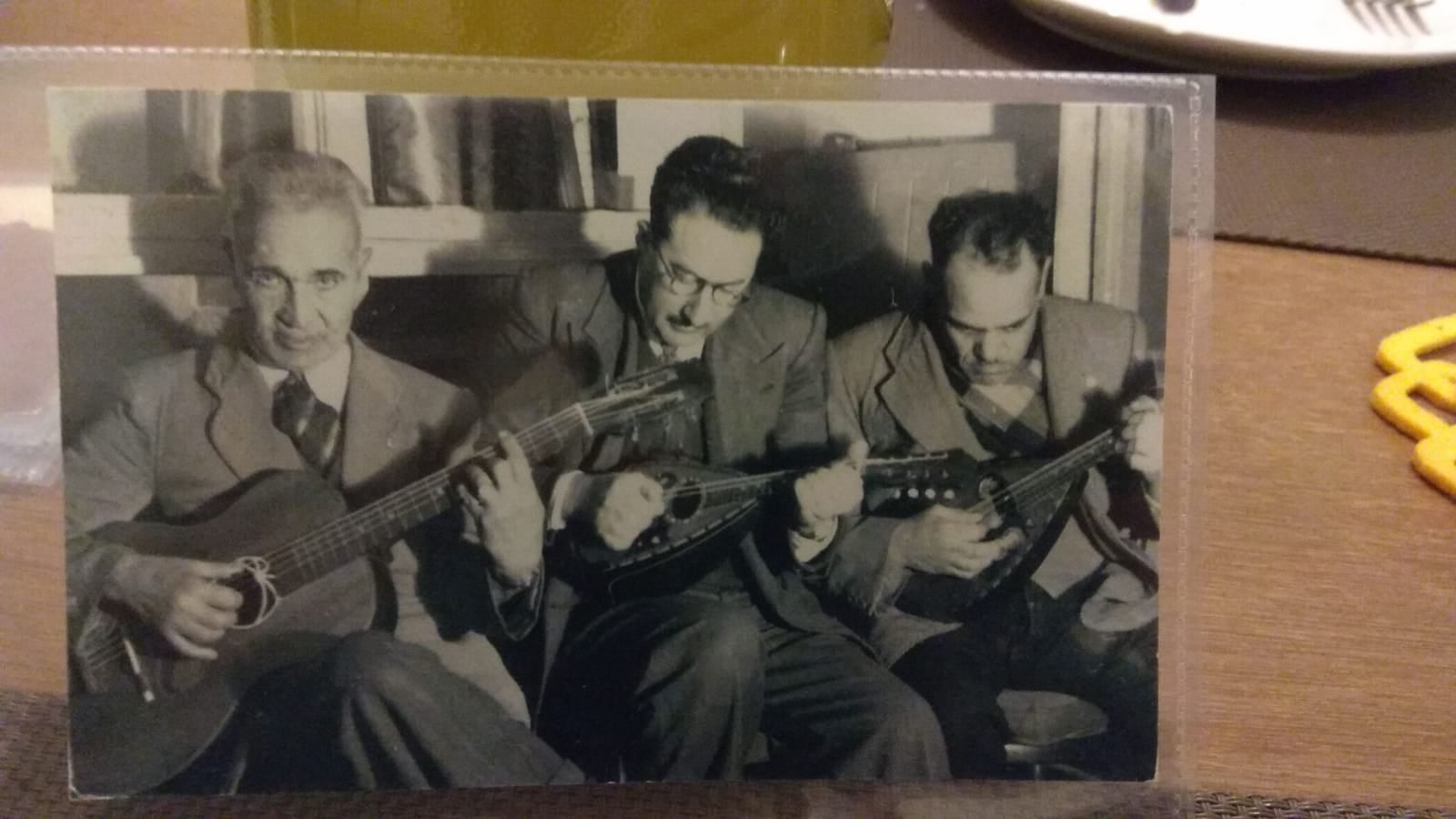

The earliest għana vocal recordings – a captivating documentation of extreme musical, historical and socio-political importance within the local landscape – all came about thanks to Malta-based Jewish entrepreneur Fortunato Habib.

Habib commissioned the first recordings of Maltese għana in 1931 when he sent a team of five local musicians to sail from Valletta to Tunis. They were the first Maltese people to ever set foot in a recording studio. Here they produced fifteen 78rpm shellacs, which were then released on the German Polyphon label.

These acclaimed singers, ix-Xudi, il-Pratu, is-Semenza, Watty Cachia and Antonio Teuma Castelletti, were accompanied by the talented guitarist Giuseppi Prato. These fifteen records were sold locally and within Tunis' and Alexandria's Maltese community, through the Bembaron and Cie store.

Shellac records are unfortunately overly fragile – they are effortlessly broken, damaged and at times even destroyed, meaning that these invaluable pieces of local history are scarce, to say the least. Filfla Records have recently restored and rereleased these records.

The musicians, Juann Mamo via Facebook

The musicians, Juann Mamo via FacebookThese records commissioned by Habib meant that Maltese singers for the very first time in history, saw their name printed on a record like their foreign counterparts.

This ushered in a strong sense of identity and pride for the lower class, as it was the first time that they could relate and listen to music in their true language and dialect on record. This came at a time when Malta was tainted by bitter socio-political frictions over whether Italian or English should become the island's official language.

When listening to these records, one can note the occasional English or Italian word tossed in, accentuating the manifold layers of Maltese culture and vocabulary at the time.

The Evolution Of Għana

Pre-World War II għana was ritualistic, performed during daily chores to while away the time and was sung by both men and women. It was also accompanied by numerous instruments. Post-war għana saw a decline in female għannejja and the Bormliża technique, as the spirtu pront variety became steadily popular and men took over the art of għana and transported it to bars and każini.

Post-1953 għana is only accompanied by one to three guitars and holds rhyming and lyrical originality at a higher importance than pre-WW2 għana. The true catalyst that brought about this shift was none other than Ġużè Cassar Pullicino when he organised the first-ever Maltese Folklore Festival in 1953 – an event which inadvertently altered għana and Maltese culture forever.

An għana competition was arranged as part of the festival and failure to rhyme, subject deviation and going over the stipulated time limit were among the penalties of the competition. The quality of voice, diction and subject knowledge were prized during this contest. Soon, għannejja started adopting the Maltese Folklore Festival contest rules consistently, even when performing among themselves, making the festival a prompter of change.

Interestingly, the Maltese Folklore Festival also brought with it a cultural metamorphosis in Malta, as the middle and upper classes ceased to regard għana as a nefarious lower-class pastime. Now that it was part of the intellectually-backed Maltese Folklore Festival, għana became a valued part of our country's tradition. This epiphany changed the way għannejja were treated too as they ceased to be seen as lowly people – the għannej was now the protector of culture and tradition. The singers were now getting the attention of local intellectual circles, being asked to perform at cultural festivals and renowned hotels and were also sent abroad to represent Malta in cross-cultural exchanges.

It was at this time that għana became mythologised as the soul of Maltese tradition which had to be safeguarded at all costs. Being an għannej wasn't a matter of having a hobby anymore. After 1953, these singers were looked at as vocational guardians of culture who kept our national essence alive.

Għana kept soaring high in popularity, with its elevation skyrocketing in the 90s, when lauded writer Frans Sammut wrote numerous għana operas to be performed in local theatres and public gardens. These became part of the Iljieli Mediterranji Festival which in 1994 took place at the Argotti Gardens. For this edition, Sammut wrote an għana opera named Mannarinu, which told the story of the insurrection of the priests of 1775.

Sammut produced another għana opera in 1995 titled L-Atti ta' L-Appostli, which recounted St Paul's journey through the Mediterranean in għana form. Sammut, ingenious as ever with penmanship and prose, made use of għana's many faces to create a genuine performance that made use of both sombre and spirited għana techniques to narrate the opera's tale in an emotionally evoking manner.

In an interview about L-Atti ta' L-Appostli, Sammut was cited as saying "What should really be said about għana is that it is a genuinely Mediterranean form of song which carries visions of orange groves and deep blue waters." He went on to state that għana is the most emblematic musical form there is.

A Love Lost

Over the years, għana's popularity dwindled, it was gradually bypassed and assumed near-dead. It could be reasoned that this was primarily due to the development that Malta went through in the last five decades when it comes to amusement places.

However, some scholars also argue that the art of għana was near-lost due to an intrinsic lack of interest the Maltese people have towards their heritage – regularly shunning away and spurning cultural individuality in favour of generic Western and internationally widespread forms of entertainment.

A Reawakening

Nowadays we are seeing a reemerging appreciation of Maltese culture in the younger generations – from an interest in the għonnella to a new-found love for Maltese food and a deep love for Maltese townhouses and even an interest in our language. We are currently living through a cultural renaissance – a newfound fondness for our nation's vocal articulation – għana, għannejja and the intangible heritage they preserve and protect.

As of 2021, għana was finally given the recognition and honour it has always merited. It was added to the List of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO.

Thanks to this newfound appreciation, one can regularly attend breathtaking live għana performances in numerous bars and każini around Malta – particularly on Sunday mornings.